I’ve been thinking about empathy. It’s something I’m not short of, I think – short as I am of so much that is useful for life in the 21st century :-) - and this is both a blessing and a curse. Partly it’s innate, a matter of temperament, goes with being quiet, introspective, imaginative; partly, I think, the result of growing up the held-close only child of a mother who craved understanding and sympathy and cast me in the role of providing them. Of course, a capacity for empathy is important, desirable and essential to decent, caring co-existence on any scale from the familial to the global. Of course, to a certain level, it’s entirely to be approved of and encouraged. But perhaps you can have too much. It can paralyse. It can make life too hard.

I can’t imagine being a nurse or doctor. Not because I’m squeamish about blood and entrails – on the contrary, a certain creepy fascination there. More because I feel I would absorb everyone’s pain and be incapacitated by horror and sadness. Perhaps this is not entirely true, and I could become accustomed. I suspect I could not become sufficiently accustomed. So it’s clearly a very, very good thing not everyone has the same temperament and susceptibilities. I know a woman who is a nurse on an acute psychiatric ward. She’s gentle and patient, but about as lacking in empathy as anyone I’ve ever known, seemingly without any capacity to imagine or curiosity to know what it is like to be another. I rather think this is part of what makes her good at the job, able to be there day after day, kind and present and gently interested and only occasionally overwhelmed.

I speak in extremes, of course, where there are only subtle gradations. I know that not all nurses and doctors, and others who live and work daily with extremes of suffering, are like that woman, that some, perhaps the best, do have enormous empathy, but have learned a difficult, blessed skill of standing aside from it when that’s what needed. I absolutely do NOT mean to say: I cannot do this because, oh, I am so sensitive! it’s harder for me than it is for someone else! How can I ever know (I’m not THAT empathetic) how anything feels for someone else?

I speak in extremes because I know why I seek empathy in others and value it – no question there - but need to focus on what is problematic about it.

Someone I care about had some terrible news recently, you see. I feel for them. Their face, their fear, are in my mind and heart all the time. So much that I am paralysed by my feelings, sliding away from them into depression, and scarcely able to function. This is hardly a state where I can be there for a dear friend just at the time they may need it most, is it? So my empathy, my sensitivity - which on the whole I do value, although they make life difficult – have been feeling like something I need to get a different handle on, in order to deal with this tough stuff, the kind of tough stuff that happens to all of us sooner or later.

I don’t want to be unfeeling. I don’t really want to be different from who I am – what a fruitless desire that would be, anyway. But to have a different relationship to these strong feelings of empathy, connection. My Buddhist teachers would speak, I think, of experiencing them in a broader context, a deeper container; that resonates, certainly, but I think I have grasped it only intellectually, not experientially.

There’s an oft-repeated story about the Dalai Lama that both moves me and makes me cringe. It is said that he once attended a peace conference in Northern Ireland; that, while the bereaved and maimed and the repentant gave their testimonies, he was seen to lay his head on the shoulder of an aide and weep continuously; that shortly afterwards, at a press call, sandwiched between two grave, white-bearded bishops, he laughed delightedly, reached up and tweaked their beards. No one who knows him thinks him superficial; that his tears, because they dissolve so fast, come too easily and mean nothing. Somehow he is able to hold both intense suffering and… well, and everything else along with it, so there is not just the suffering. This is so difficult, so foreign to anything I've ever experienced – I think that is why I cringe.

I cringe too, though, at my own inability to keep living in the knowledge of something hard and sad and terrible, except by numbing myself. I don’t want to numb myself. But I do want, and need, to keep living, not to only be in pain in sympathy with someone else’s pain. How did I get to such an advanced age with so little idea about this? Is it too late to learn another way?

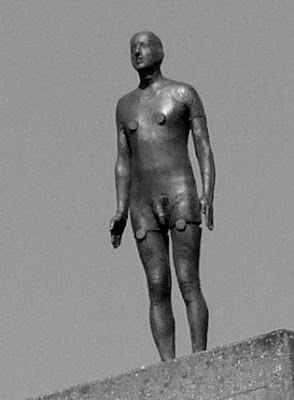

"I don’t agree with Louise Bourgeois's famous saying that art is a guarantee of sanity. For me it’s much more a sharing of anxiety than anything to do with catharsis. It doesn’t relieve, but amplifies and shares anxiety. By making objects that carry my uncertainty, I learn to hold it, as a vehicle for sensitivity.

"I don’t agree with Louise Bourgeois's famous saying that art is a guarantee of sanity. For me it’s much more a sharing of anxiety than anything to do with catharsis. It doesn’t relieve, but amplifies and shares anxiety. By making objects that carry my uncertainty, I learn to hold it, as a vehicle for sensitivity.